THE POET’S FLOWER

A Thousandworld Story

By Joseph A. Davis

Introduction: About Thousandworld

In Thousandworld, creativity is power.

Thousandworld consists of countless domains – small worlds made by artists, musicians, poets and others who have honed their abilities to the point that they can work wonders. Such people are called “creators”, as traditionally, their talents are seen as reflections of the Great Creator.

Paradisum, where the following story takes place, is among the greatest of Thousandworld’s domains. Originally created by the sculptor Angelica Skogsbergh, it has been ruled by the mighty poet Pallantu ever since Angelica’s demise at the hands of the darkenwraiths. Paradisum, a safe haven for refugees displaced by the ravages of these shadowy monsters, is also home to the Academy, where young people from all of Thousandworld train to perfect their creator talents.

In the pages that follow, you, the reader, may share in the adventures – or misadventures – of one of the Academy’s students, a young man named Zardrin. His life is full of possibilities. Will he woo his lady love, restore the glory of his disgraced family, encounter a legendary creature said to have vanished long ago, or perhaps do battle with the darkenwraiths? Your choices will decide his fate.

*

Readers of Adventures in Thousandworld will recognize some of the characters who appear along the various branches of this story. These characters may be slightly younger than the observant reader remembers, as the following events take place approximately two years before those related in The Darkenstar.

THE POET’S FLOWER

By Joseph A. Davis

While the other students shoveled manure, Zardrin quietly snuck off to recite poetry to his flower.

Going unnoticed might have been one of his creator talents if any class here at the Academy taught that kind of thing. He had certainly escaped the notice of most of the young women in this gardening class for the past two years, in spite of what his grandmother had assured him were particularly aristocratic looks. His shock of red hair was a hallmark of her side of the family, and as she had told him many times, his piercing green eyes were the kind of thing one read about in the great romantic epics back in their home domain of Igru. The prominent gap between his teeth was, according to her, the mark of a passionate man, a feature shared by a distant ancestor who had once ruled over Igru’s wild and beautiful northern hill country. And what did it matter if he was a bit short for his eighteen years, with a slightly stocky build and a whole rose garden of pimples dotting his pale face? All these things were merely signs that he was in the bloom of youth and health. And besides, his poetry was enough to make any woman, young or old, swoon.

It was certainly enough to make a flower grow. Zardrin studied the delicate blossom that he had hidden in the gloom under the cat-shaped topiary. The sculpted shrub, tucked away in a less-frequented corner of the Academy’s great hedge maze, had been the perfect hiding place. It had provided just the right amount of shade to ensure that the rare doveflower’s long, white petals maintained their pale color and took on the graceful, downward-sweeping form that one read about in the great romantic epics. And the poems that he had recited to the little plant every day for the past three months, in old Igru, the most romantic of all of Thousandworld’s languages, had done their work as well. The flower, which was not supposed to take on full bloom before a year had passed, had grown up four times as fast.

In fact, it had grown up too fast. As Zardrin cupped his hand around the delicate flower and whispered his daily poem to it, he was struck by two thoughts. First, that the flower was ready, and if he did not pick it and prepare it in the next few days, it would shut its petals and swell into a bitter, poisonous dovefruit. Second, that he, unlike the flower, was not ready. But ready or not, he would need to propose this week or miss his chance.

The day’s poem was a brief one, just ten simple lines about his beloved’s lustrous black hair, warmed by the sun. Yet it took him longer than usual to recite it, with all his stumbling hesitation. Still, he could feel the creative force of his talent flow into the little plant as he spoke, warming it.

Footsteps crunched on the gravel path behind him just as he finished, and he stifled a curse. The flower’s hiding place was lost. Whoever had discovered him was sure to check under the shrub to see what had occupied him under here.

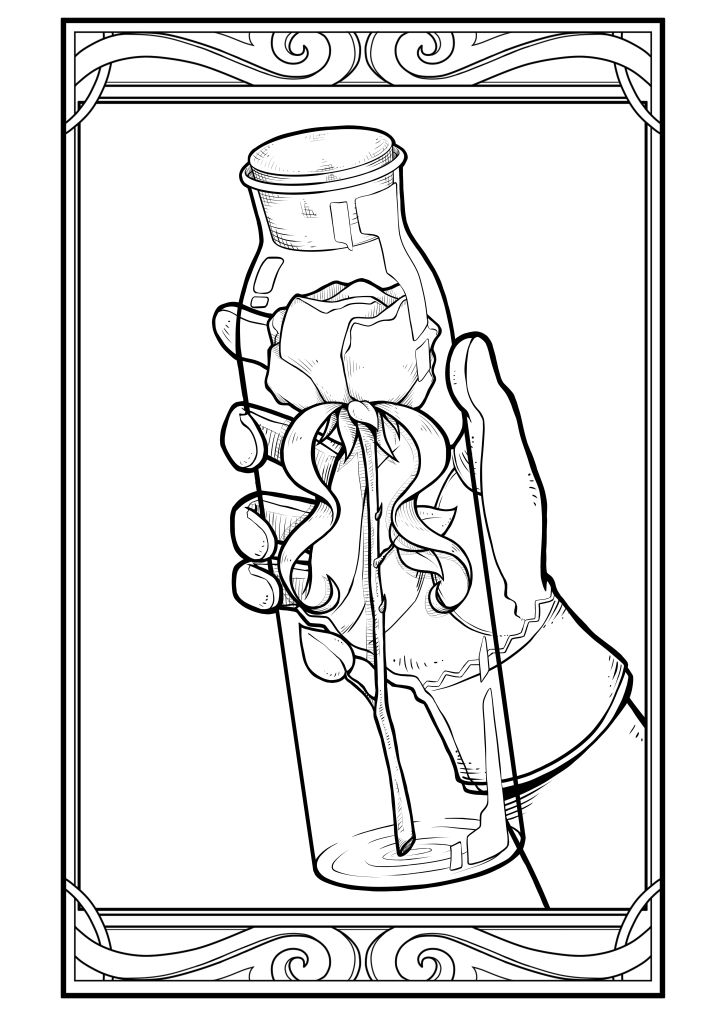

With no other choice, he hastily drew the red-tinted glass jar from his leather bag, unstoppered it, snapped the crisp stem and bottled the flower. His situation had now become even more urgent. He had mere hours to soak the flower in the traditional wine bath before it wilted, and then he would have a single day to present it before it blackened.

“Zardrin?”

He froze. It was Flua. Her voice, normally as mild as a summer breeze and as sweet as fresh-picked honey oranges, was unusually tense. Realizing that his bottom was sticking out from under the hedge in a position that was unlikely to be particularly flattering, he hastily scrambled to his feet and turned to face the woman who had made him a gardener. For it was she, his enchantingly beautiful young professor – at most a handful of years older than he – who had inspired him to choose this particular course of studies. His mother had been deeply disappointed that he had not chosen poetry. His grandmother, however, had understood as soon as she heard one of his poems about Flua’s smooth brown skin and her dark, glittering eyes, like twin pools he longed to drown in.

At the moment, those dark eyes were looking particularly willing to drown him. But not in the poetic way that he had longed for. He swallowed.

“So, Zardrin,” she said. “What exactly have you been doing while your classmates have been hard at work spreading fertilizer?” She spoke to him in Sulallian, the common tongue, even though she was a fellow Igruan.

“I beg your pardon, Flua,” he replied in their native language.

“Professor,” she corrected, still in Sulallian. Then her gaze turned down, to about the level of his hands, and her eyes narrowed. “What is that?” she asked.

Zardrin realized, to his horror, that he was still holding the jar containing the doveflower. Any Igruan would know the rare flower on sight and understand its romantic significance, and Flua was an expert in the area of plants. With a silent prayer to the Great Creator that the red glass would hide baffle her sight, he stuffed the bottle into his leather gardening bag. “Oh, it’s nothing,” he stammered. “I’m sorry, Flu- Professor. It won’t happen again.”

And it wouldn’t. The flower was picked, and his poem for her was written. He just needed to soak the flower in the traditional wine bath and then find the right moment to propose, sometime in the next twenty-four hours.

“You and I will have a talk about this later,” Flua said sternly. “But at the moment, we have more pressing matters. Pallantu is here.”

“The Speaker?” Zardrin stammered. “Here? At the Academy?”

“Here in the garden. Perhaps you will be glad to hear that the fertilizing is canceled for today. He is taking over the last hour of the lesson. And you are late.”

Her words made Zardrin quake. If his mother were to hear that he had incurred the irritation of this domain’s chief creator, the speaker of the Council, the founder and name-giver of the capital city Pallantor … And meanwhile, the doveflower in his bottle desperately needed to be soaked in wine before it wilted. After about two hours, it would be too late, and his chance to propose would be ruined.

Should Zardrin ….

Hurry back to the others and take part in the lesson?

HURRY BACK TO THE OTHERS AND TAKE PART IN THE LESSON

Zardrin had rarely seen Flua hurry, but if there was an occasion for it, it was surely a visit from the speaker. He trotted to keep up with her. Perhaps a run through the gardens together would have been romantic, if it had not been for the anxiety over his doveflower and the growing dread of what might happen when he arrived late to the lesson.

At last they turned a corner and saw him. Pallantu stood in his silver-embroidered white finery, tall and regal with his immaculately-groomed black hair crowned with a silver circlet. His long, elegant fingers gleamed with rings as he raised his hand to greet the approaching professor and student. He looked like the embodiment of the kind of nobility that Zardrin’s grandmother had always tried to convince him that their family belonged to, and now, as Zardrin stood before the speaker, it was as if he saw how hollow the old woman’s words were. He was nothing next to this man. Even his poetry was nothing compared to the mighty wordcraft of Paradisum’s chief creator.

“I see your final student has chosen to join us,” Pallantu said with a slight smile. It was first then that Zardrin noticed the hulking, white-clad guard, armed with a poleaxe, standing directly behind the speaker.

“Speaker, I beg your pardon,” Flua stammered. Zardrin had never before seen her nervous. His love wrestled with his fear, and he considered chivalrously stepping forward and taking the blame. But as he took his step, Flua stopped him with a firm hand on his shoulder. “I was not expecting your visit,” she went on, “and my student was tending to a plant in another part of the garden, on my orders.”

“No matter,” the speaker said with a dismissive wave. “The whole class is finally here – including the poet.”

Zardrin’s mother had once lamented that Pallantu had no idea who they were. Finding out that the opposite was true should have been a proud moment. But as the speaker fixed him with a piercing blue gaze, he felt only a sharp pang of terror. He looked down.

“I am here for one reason,” Pallantu announced to the assembled students, his voice strong, clear and commanding. “My new general Kareth has been granted a fortress of her own. Work on it is to be carried out by the most talented creators this domain has to offer, young or old – and that includes work on its garden. Does the Academy have any plants that eat flies?”

“A number of them,” Flua said hurriedly. “We have gluestem, witch’s goblet, swallowthorn …”

“All of them are forbidden for this test,” Pallantu said. Though he did not raise his voice, it emanated from him with such power that it was as if Flua’s words were simply erased out of the air to make room for his.

Zardrin tried to say, “Test?” quietly, but the word did not manage to leave his mouth.

The only words to pierce the sudden, oppressive silence were Pallantu’s. He cleared his throat and recited a poem about daggerflies.

Zardrin’s jaw dropped as he listened. The poem was short, simple and perfect. More than perfect, it was powerful. He could practically feel the air vibrate with the speaker’s considerable creative power as he spoke the few lines. And when he had finished, his recitation was cheered by a droning chorus of daggerflies.

A minor panic broke out among the students as a buzzing brown cloud descended upon the garden. “You may each choose one plant,” Pallantu said, his voice cutting through the rising chaos. “By the end of the hour, the student whose plant has killed the most daggerflies will be chosen for the work, which will start tomorrow. You may begin.”

As soon as he had finished speaking, the students ran en masse toward the shed where the protective gear was kept.

As Zardrin hastily donned long gloves and a wide-brimmed hat with a face net, it occurred to him that he knew the perfect plant, and the perfect way to turn it into a deathtrap for the stinging insects. However, it also occurred to him that there were both advantages and disadvantages to being selected for the Speaker’s prestigious assignment.

On the one hand, it would be a way of getting his family noticed, gaining some level of connection to Paradisum’s most powerful man. He could make his mother’s dreams of restored family honor come true.

On the other hand, it would also mean missing the field trip to Bloomington tomorrow – which would likely be the perfect occasion to get a romantic moment alone with Flua to make his proposal. He would certainly not get many other chances before the doveflower blackened in its wine bath – which he had less than two hours left to provide before it wilted.

Should Zardrin …

TRY TO SUCCEED AT THE TEST

Zardrin knew that daggerflies were attracted to sweet, slightly pungent scents. As a child, he had helped his grandmother create a number of daggerfly traps that were no more than bowls containing the right mixture of syrup and vinegar. The daggerflies came to drink the mixture, got stuck and died there.

The Academy’s garden had a large, elegant fountain flower which – with enough poetic coaxing – might just serve the same function.

While his classmates gathered gardening tools, fertilizers and watering cans, Zardrin hurried off into the hedge maze. The only tool he needed was his words.

The fountain flower, which grew floating in a massive marble basin near the edge of the maze, was truly a thing of beauty. Its broad blue petals floated just under the surface of the water, spreading as wide as Zardrin could reach with his arms outstretched. Its green stem, as thick as his wrist, constantly pulled water up from the basin and sent it trickling from the four points of its leafy crown, back down into the basin.

The flower’s nectar already made the water slightly sweet, like an extremely watered-down cordial. The question was what effect Zardrin’s poetry could have on the process. This was not a plant that students usually worked with.

Composing a poem to make the nectar sweeter was no difficult task. Sweetness was a common theme both in gardening and in romance, and Zardrin could produce poems about it as easily as breathing. It was the sharpness and the stickiness that were the challenge, as well as the amount of raw creative power he would need to pour into the words. There was a lot of water in the basin, and the fountain flower had less than an hour to transform it all.

As Zardrin began to consider lines about sharpness, vinegar and fermentation, he realized that this was going to require a creative effort unlike any he had ever before exerted.

But it would be worth it to gain the speaker’s favor. As Zardrin began to recite his first poem, he imagined the expression on his mother’s face when she heard that by choosing gardening against her wishes, he had managed to impress Paradisum’s chief creator.

But first, he would need to succeed. Zardrin thrust the thought of his mother aside and focused on his recitation. He closed his eyes and poured his creative power into his poetry. Even with his eyes closed, he could sense the plant responding. After a few grueling minutes, he could smell it responding, as well. The scent was clearly sweeter now, but it did not yet have the necessary pungent notes.

With an inner effort that made his voice and his body shake, he reached deep into his creator talent and poured raw creative power into a poem about fermentation. After a few minutes and several lines about sweetness ripening into pure intoxication, the sweet smell took on a sour edge. Soon the first daggerfly landed on the surface of the water, which was now turning a cloudy shade of brownish-orange. Unfortunately, the insect managed to fly away after filling up on the nectar-filled water. Zardrin needed to make the fountain flower thicken the liquid, make it stickier. He redoubled his efforts.

A few poems about honey and syrup later, the surface of the water was dotted with dead and dying daggerflies. At last Zardrin could relax and watch the fountain flower, which he had turned into a death trap, do its work. It occurred to him, as he watched daggerfly after daggerfly land among its drowned fellows and drown with them, that they were very short-sighted creatures, so eager to taste the sweet water that they missed the danger right in front of them.

“My fountain flower!”

The sweet music of the voice made Zardrin’s heart leap, and he turned to face his beloved. It was not until he saw the utterly distraught expression on her face that he realized what she had said. He whirled to face the fountain flower and found that its thick stem, once green and healthy, had yellowed, and that its flow had slowed to a few threads of sticky brown ooze. It occurred to him that the Academy’s garden only had a single fountain flower. It was an exceedingly rare plant.

“I, um, I’m sorry,” he stammered.

“For what?” The speaker’s voice cut off Flua’s response. Pallantu strode out from behind a hedge, seemingly unbothered by the buzzing of the few remaining daggerflies, and surveyed the fountain. “The plant’s life is in peril,” he observed. “But the lives of the daggerflies have ended. Victory seldom comes without a cost. An important truth to remember while we are at war.”

His gaze fell on the young professor, who looked down at her feet. Zardrin tried to think of something to say, some way to intervene and take her side, but his suddenly dry mouth refused to form any words.

“It was a clever strategy,” the speaker went on. “Imaginative, insightful, a testament to creative power both considerable and well-used – but first and foremost, it was effective. You have won, young poet. Tomorrow will be your first day of working on my new general’s garden. After three days, your work will be evaluated, rewarded, and perhaps extended, according to its quality. My bodyguard will meet you outside the Academy after breakfast.”

For a moment, Zardrin felt as if he were floating. Mother’s dream was going to come true. His chest swelled with the pride of restored family honor, and he could practically taste the celebratory feast. He had won the favor of the speaker. Or at least, he could win it if the three days of work went well.

Could this also help to win Flua’s favor? When she saw that he had impressed Pallantu, how could she fail to be impressed as well?

But once the speaker had left, Zardrin turned to his beloved and found that she had eyes only for the tortured fountain flower. “Class is dismissed,” she said to Zardrin, and he could not miss the clear note of sorrow in her voice.

At the same time, he suddenly remembered the doveflower in his bottle. He did not dare pull it from his leather gardener’s bag to check on it – not in front of Flua. But if everything he had learned about the flower was correct, he had at most a single hour to soak it in the wine bath before it would wilt.

Should Zardrin …

Stay behind to help with the fountain flower?

Hurry to find some wine for his doveflower?

HURRY TO FIND SOME WINE FOR HIS DOVEFLOWER

Flua was clearly troubled. But, as one of the great romantic poets had once written, love was pain’s cause and its cure. She would not be worried about mere trifles such as fountain flowers when Zardrin recited his poem for her and presented her with the traditional proposal gift.

Now he just needed to make that happen. He hurried home. Or, rather, he could hardly call the relatively humble villa where his mother and grandmother lived “home” – but he hurried to his grandmother. She would have the right Igruan wine to soak his flower. She must!

The run across town was torture. Zardrin had never been an athlete, and as he puffed along, clutching his leather gardener’s bag and its precious cargo to his chest, he cursed his burning lungs, his weak legs and his pounding heart and urged them to go faster.

At last he collapsed against the front door, practically falling into the entryway as it opened. “Grandmother!” he gasped. “Wine! I … need …”

His aged grandmother rose from her chair and limped toward him with a concerned expression. “Zardrin, my dear! What’s happened to you? You’re –”

“Grandmother!” he pleaded. “Wine! The flower …” He could hardly hear the thin squeak of his own voice over the violent pounding of his heart, which threatened to burst within him.

A look of realization flashed across the old woman’s wrinkled face, and she turned and staggered towards the kitchen as fast as her frail body could carry her. As Zardrin wrestled with the clasps of his leather gardener’s bag and dug out the red glass jar, his grandmother came limping back with a green bottle that she was in the process of uncorking.

“You did it!” she crowed. “My Zardrin! A real doveflower! And now you’ve picked it!”

The red jar’s large cork sat tightly. Zardrin strained against it with all the remaining strength in his spent body.

“She will be completely swept off her feet,” his grandmother continued. “It will be a proposal worthy of the romantic epics. And that poem you’ve prepared …”

Zardrin managed to remove the cork, and his grandmother’s words faded into the background. He stared down at the flower. His vision began to cloud over.

His grandmother, finally arriving with the uncorked wine bottle, froze, her eyes fixed on the contents of the jar. “Oh, Zardrin,” she said. “My precious boy. I am so sorry.” She put the bottle down on the floor and embraced him.

Zardrin hardly realized that she was there. His eyes were fixed on the flower. Its two proud, wing-like petals had drooped and turned brown.

“I’m too late,” he found himself mumbling, unsure if it was the first time or the tenth that the words had left his lips. His grandmother was holding him close, stroking his hair, wiping his tears with the long, flowing sleeve of her dress.

“Oh, Grandmother!” he wailed. “I wanted her so!”

“I know, my boy,” she said, stroking his back. “I know.”

“The flower – it wasn’t supposed to wilt. It was supposed to be perfect. She was so beautiful. Oh, take me home, Grandmother!” he cried. “I don’t want to be in this domain anymore!”

“I know,” she said again.

When Zardrin had cried as a little boy, his grandmother had often read to him to comfort him. But now it seemed like there was nothing to read, no words but, “I know.”

He continued to speak anyway, feverishly. If only Flua hadn’t surprised him and forced him to harvest the doveflower before he was ready. If only he had waited and recited his poem to the little plant after class instead of sneaking off. If only he had run home faster. If only Pallantu had not come to present his challenge to Zardrin’s class. If only Zardrin had not won …

His mother came rushing out into the entryway. “What is it, my son?” she said. “What has happened to you, and what is this talk of Pallantu? Have you incurred the wrath of the speaker?”

Zardrin told her about his victory through tears, lamenting the whole time that it had happened, that the Great Creator had not intervened to keep him from participating, or to keep him from winning, or to strike him dead.

“Zardrin!” his mother’s voice cut through his lament. “Do you know what this means?”

“Nothing,” he muttered. “My flower has wilted. I’ve lost. It all means nothing.”

“Think, boy!” she said. “The speaker has acknowledged your poetry! Do you understand what this means for our family?”

“Our family line will end with me,” Zardrin announced.

“Ah, but think of your gardener girl,” his mother said. “When our family’s glory is restored, you won’t need a doveflower to propose to her – or to any other woman, for that matter. Wealth and honor speak louder than flowers, Zardrin. If you manage this well, you can have any woman you want.”

Should Zardrin …

Keep sulking? (THE END)

Focus on tomorrow’s assignment?

FOCUS ON TOMORROW’S ASSIGNMENT

A great Igruan poet had once written that toil was a deep hole into which endless time and passion could be thrown.

So it was with Zardrin’s mental toil. He had never actually been a serious student of gardening – honestly, he had never felt the need to understand plants, since he could manipulate them with his poetry quite effectively without understanding. And of course his reason for joining the gardening class had not had anything to do with plants.

But the prestigious assignment Pallantu had offered him would be all about plants. After inadvertently poisoning the fountain flower and failing to soak the doveflower in time, Zardrin resolved firmly not to let any such mistake jeopardize his chance to win the speaker’s favor. And so he hurried to the Academy’s library to learn as much about plants as he could before dawn, scribbling frantic notes and casting his hours and his thoughts of Flua into the deep hole of academic toil until the librarian finally doused the lamps.

He missed breakfast the next morning – a first for him – but managed to get himself dressed and ready in time to meet Pallantu’s white-clad bodyguard outside the Academy’s front entrance.

The man arrived in a beautiful black carriage drawn by horses of living white marble. Exiting and seeing Zardrin, he held the door open and beckoned for him to climb in. Zardrin stared at the magnificent vehicle before doing as he was bidden. As they rolled along Pallantor’s broad white streets, Zardrin tried to imagine his mother’s expression if she could see him now, publicly escorted by the speaker’s own bodyguard in a carriage worthy of a king. It was so seldom that he had seen her proud and happy during his childhood – more often, she had been proud and wounded, or proud and demanding, or proud and despairing. He couldn’t help but try to imagine Flua’s expression, too. Perhaps rumors would spread, and she would hear that one of her students had been escorted to the general’s keep in this magnificent manner.

Pallantu’s bodyguard was like a hulking embodiment of the capital city’s great white walls: tall, imposing and completely resistant to Zardrin’s uncomfortable attempts to make conversation. So as they passed through the city gate and rolled on across the countryside and through the forest, Zardrin had plenty of time to try to review what he had learned during the night. He pulled his hastily scrawled notes from his gardener’s bag and went through them again and again, trying to memorize everything from watering needs to advanced pruning techniques for all the most rare and expensive plants he had found in the books – the kinds of plants likely to be found in a general’s garden in Thousandworld’s largest and most powerful domain.

However, once they had finally arrived and he had been shown to a far corner of the hedge maze and given his task by the chief gardener, he found that his hours of study had done nothing to prepare him.

He was to work with a single plant, and it was not at all what he had expected. Rather than some rare and delicate foreign flower, it was a Paradisian needlebush of the kind that students at the Academy used for sculpting topiary. This one had been formed into a particularly wicked-looking spider only slightly smaller than Zardrin himself, complete with sharpened wooden fangs. The sculpted shrub had been uprooted, and it lay on its back with its root exposed and its eight leafy legs pointing heavenward. But Zardrin’s task was no simple transplantation. Rather, he was to give the plant the hardiness to survive being uprooted and the ability to root itself again when necessary. And he was to make it deadly.

As the head gardener left him to his task, Zardrin quailed at its impossibility. He imagined his mother’s crushing disappointment once his work had failed to satisfy Pallantu. If he had the ability to do such a thing, surely he could have kept the doveflower from wilting?

This part of the hedge maze was a noisy place, too close to the din of construction on a stone wall. So Zardrin helped himself to a wheelbarrow, loaded the great spider into it and wheeled the thing off to find a place where he could focus on the problem in relative peace.

Soon enough he found a spot that was both quieter and more beautiful, a series of small, hidden gardens with lovely fruit trees and peaceful little ponds. He unloaded the spider in the shade of a cloudapple tree, sat cross-legged in the grass beside it and frowned at it thoughtfully.

He sat there for a long time, studying the plant and considering what kind of poetry could make it hardier. That should be his first priority, keeping it alive before trying to make it deadlier. The second part of his task was a bit uncomfortable to think about. Deadlier meant more able to kill. But to kill what? They were at war with darkenwraiths, creatures that no ordinary shrub or poetry could do anything against. He did not know if they could be killed or if they even counted as alive. So what was this spider shrub meant to kill?

As Zardrin pondered the question, his thoughts were interrupted by the gentle sound of sobbing.

Quietly, he rose to his feet and followed the sound to a luxuriant flowering bush. On the other side of it, a young woman sat on an ornate bench by the edge of a small pond. Her long, blond hair hung down around her face, which was buried in her hands, and her shoulders, adorned with the puffs of a light blue dress fit for a Lantonian noblewoman, shook.

Should Zardrin …

FOCUS ON HIS WORK

Zardrin was good at moving undetected. Not wanting to disturb the young noblewoman, he took the spider shrub and quietly carried it off to another part of the hedge maze, leaving the noisy wheelbarrow behind.

The stranger’s tears led his thoughts to moisture, which a Paradisian needlebush would normally absorb through its root. But there were certain plants, including somw Lantonian flowers from the mountain mist forests, that absorbed most of their moisture through their leaves. Could he train the spider to do the same?

A few hours and several poems later, the topiary spider was thriving. Or, it looked no worse, at least. And he had felt as if his creator talent were having some effect. Now it was just a matter of making the spider deadly. The natural thing seemed to be to try to coax it to produce venom for its fangs, but the thought of being the cause of some intruder’s death made him uneasy. Perhaps a tranquilizing toxin, like the one found in Tijian sleep blooms?

Zardrin worked hard for the rest of that day, and the next. By the end of the third day and with the help of some of the other gardeners, he got the spider walking. The chief gardener was so elated that he sent for the general, who came out to see the wonder.

Zardrin was amazed to see the chief gardener return with a tall, blond woman no older than he – the noblewoman he had seen crying by the pool! But now her tears were gone, replaced by a stern, confident expression, and her blue dress had been exchanged for a black and white uniform. At the sight of the large topiary spider crawling back and forth in a ring of gardeners holding it at bay with rakes, her pretty face lit up in a wicked smile.

“This is brilliant work, young …”

“Zardrin,” he supplied. “Of the Igruan house Balador,” he hastily added.

She raised an eyebrow in a manner that reminded Zardrin, uncannily, of Pallantu. “Zardrin of house Balador,” she said. “A nobleman with a potent talent and a sense for the more … creative side of warfare. The speaker will be informed of your success here. I intend to personally request that you be assigned to my fortress as Master of Topiary. The speaker will not deny my request. You and your house will be recompensed handsomely.”

Zardrin smiled, imagining his mother and grandmother dressed the finery of Igruan nobility, being driven around the city in a luxurious carriage like the one he had ridden in. And he imagined how Flua would react to the news that one of her students had achieved such an honor.

Perhaps he wouldn’t need to spend another three months growing his own doveflower. They were rare and expensive, but, as one of the more cynical poets had written, everything could be bought for a price.

Behind him, one of the gardeners cried out as the topiary spider got past his rake and sank its wooden fangs into his foot.

The general laughed.

THE END

TRY TO COMFORT HER

Zardrin resolved to do his best to comfort the young woman. He had little direct experience of this kind of thing, but he had read plenty of romantic epics about it.

“Fair maiden,” he said, stepping out from behind the bush, “tell me of your distress, and if I can I will assuage it, whether by deed of sword arm or deed of pen or tongue.” As he spoke, he dug his best silk handkerchief from his pocket and offered it to her.

The young noblewoman rose to her feet. She was tall, slightly taller than Zardrin but probably about his age. Her blue eyes, gleaming with tears, regarded him first with surprise, then with a flash of anger. Then, as suddenly as the anger had come, it was replaced with laughter. This was not the gentle, affected giggle of an Igruan noblewoman, but Zardrin would not call it completely cruel, either. Playful, with a mocking edge.

“I could have you executed for spying on Pallantu’s general,” the noblewoman said with a smirk that did not quite touch her eyes. “But since you can quote Galassin’s Brightblade Cycle so flawlessly, perhaps I will let you live.”

Zardrin should have been terrified. This young noblewoman was the general. But something about her smirk, or her tears, or her knowledge of Igruan romantic epics gave him a strange courage. “If by my life or death I may ease your grief, then both are yours,” he said, bowing and offering his handkerchief again.

She accepted it and wiped her face before pocketing it.

“That’s quite an offer, gardener,” she said. “Or shall I call you Sir Brightblade?”

“Zardrin,” he said, bowing more deeply. “Of the Igruan house Balador.”

“So, my gardener is both a poet and a nobleman? Come, Zardrin of the Igruan house Balador, and sit with the lady of this keep, Kareth Hallovin, Speaker Pallantu’s general.”

She pronounced the word “general” with such bitter disdain that it took Zardrin a moment to absorb the full meaning of her words and realize who she was. The daughter of the late Count Hallovin of the Lantonian highlands. It was common knowledge that the speaker had taken her into his home after her parents had been tragically taken by the darkenwraiths. Zardrin hadn’t heard that Pallantu had made her a general. But many of the speaker’s dealings were wreathed in secrecy.

It occurred to him, as he seated himself beside her on the bench, that she seemed less than pleased with the appointment.

“Your garden is truly impressive,” he said, stalling for time as he tried to find something of substance to say.

“Impressive is a small comfort,” she said. “It is a fine word, but far from words like warm, loving, or home.” She sighed. “But I suppose I should be used to settling for impressive by now. Tell me, Zardrin of House Balador, are you the kind of poet who writes poetry for the girl you love? Or do you only write about impressive things?” Her voice had a bitter edge, but here was an unmistakable eagerness in her blue eyes. If Zardrin were writing a poem about her expression, he might have used the word “hungry”, or perhaps even “starved”. He suspected that he knew what she was hungry for.

Should Zardrin …

Tell her about his love for Flua and share his poem about her?

Compose a romantic poem about Kareth?

COMPOSE A ROMANTIC POEM ABOUT KARETH

Composing a quick poem about a pretty noblewoman with shining blue eyes was no difficult feat for Zardrin. And perhaps it could comfort her, he told himself as he stood and assumed the traditional posture of recitation before her. Meanwhile, behind this thought, another lurked, one that he hardly dared to entertain. It occurred to him that Kareth really was quite pretty. And that a Lantonian countess who was close to the speaker was the kind of match his mother dreamed of.

It was a simple poem that he recited, a few lines about her golden hair and graceful manner. But she listened with closed eyes and an enraptured expression.

When he had finished reciting, her eyes remained closed. “More,” she urged. “Please, my poet, tell me more.”

Her words sent a thrill through his body, but at the same time, they made him uneasy. He pushed this unease aside and, emboldened by her eagerness, went on. The next poem was about her blue eyes, beautiful and free like the wild Lantonian skies in the mountain passes which his grandmother had told him about.

“Oh, my poet,” Kareth moaned, seeming to melt before him. “Tell me I am your Lantonian heavenbloom. Tell me that I bring light and warmth to your cold marble halls.”

One of the great poets had said that love was a bee’s nest of exquisite pain, and he heard this pain in her voice now. He let it carry him along, despite his growing unease. “My fair, golden heavenbloom,” he recited, but got no further.

Kareth Hallovin, countess of the Lantonian highlands, appointed general by Paradisum’s chief creator Pallantu, leaped from her seat and threw herself upon him like a wild animal. His poem was cut off with an awkward choking sound as her lips met his. She tangled her fingers in his hair, and a line from an old poem about love consuming like a fire flashed briefly though his mind. Then he forgot all words.

Her kisses, wild with desperate hunger, thrilled and frightened him. His lips struggled to do sweet battle, as an old poet had written, but quickly found themselves overwhelmed by the force of the general’s passion. Zardrin’s hands, which had hung helplessly at his sides, found her back, and he held on for dear life.

Then, as suddenly as it had begun, the kiss was over. Kareth released him and stood before him with her eyes squeezed shut. “Tell me that I am no general,” she begged brokenly. “Promise me that you will never send me away.”

“I, um …” Zardrin stammered. The frightening desperation written on the young woman’s face struggled in his mind with the sudden image of Flua. He had always intended his first kiss for her. Murky, sickly regret rose to quench the lingering fire that burned in his body.

“Pallantu Alaravin!” a man’s voice boomed beyond a high hedge wall. “Speaker of the Paradisian Council, chief creator of Paradisum, lord of the great city Pallantor!”

Cold fear pierced Zardrin’s heart, and he searched desperately for somewhere to flee. But before he could return to his spider plant and pretend to be hard at work, the hulking, white-dressed bodyguard who was the source of the voice appeared around the corner of the hedge wall, his wicked-looking poleaxe resting on his shoulder.

Behind him, Pallantu strode into the little garden with the regal grace of an Igruan mountain lion preparing for a kill.

“General,” he said, nodding to Kareth. “I see that you have made the acquaintance of our newest gardener.”

Kareth nodded with a meekness that shocked Zardrin. The transformation was as total as it was sudden. “Yes, Speaker,” she mumbled.

“Focus is one of the chief virtues of war, general,” Pallantu said. “I trust that you appreciate this – that you would not want to distract this young man from his important work.” Then, without even turning to his bodyguard, “Escort the general back to her keep. See that she is fed and that no one disturbs her reading. She has much to read before tomorrow’s meeting with the Council,” he added significantly, “and her focus is of the utmost importance.”

The bodyguard whisked Kareth away, and Zardrin was left alone with the speaker.

“How has your work been progressing, Zardrin of House Balador?” Pallantu inquired, his face an inscrutable mask.

“It, um, I have not made much progress yet, Speaker,” Zardrin stammered. “But I have some ideas.”

“Ideas can be dangerous things,” Paradisum’s chief creator said, his sapphire-blue eyes suddenly blazing. “Depending on their quality, they can be dangerous for one’s enemies, for one’s allies or for oneself. Henceforth, I trust that your ideas will be prudent ones. And as the general leaves you in peace to carry on with your important work, I trust that you will extend her the same courtesy.”

“Y-yes, of course, Speaker.”

“Excellent. In war, as in life, focus is rewarded and its opposite is punished. I look forward to seeing your completed work by the end of the day, as proof of your renewed focus. If you accomplish this, your reward will be appropriate compensation for a day’s labor and a safe return to the Academy.” With that said, Pallantu turned on his heel and strode back in the direction he had come.

Zareth hastily returned to the spider that lay waiting on the other side of the flower bush. He collapsed against the trunk of the cloudapple tree and sat staring at his assignment and waiting for his heartbeat to return to normal.

His mind was a chaos of images: Flua. Kareth. Dungeons. Poleaxes. The speaker’s terrifying gaze. The face of his disappointed mother.

In the midst of this whirling chaos, the full import of Pallantu’s words gradually dawned on Zardrin. The terms had been changed – rather than three days of work and a chance to impress the speaker and extend his employment, he would be safely returned to the Academy and paid for a single day of work. If he succeeded by the end of the day.

Zardrin stared down at the spider. Hardiness. The ability to root itself. Deadliness. The ability to move was implied. This was not a one-day job. And Pallantu had only told him what he would gain if he succeeded – not what would be done with him if he failed.

THE END

TELL HER ABOUT HIS LOVE FOR FLUA

“There is one woman I have written a poem for,” Zardrin admitted.

“Recite it for me.” Kareth’s words were not a request.

Zardrin rose from the bench and assumed the classical posture of recitation before her. “I should warn you,” he said, “this poem is a bit … passionate.”

“I am familiar with Igruan poetry,” Kareth said with a slight smirk.

Zardrin cleared his throat and began.

Kareth listened with closed eyes, and as he described, in verse, the beauty of his beloved and his unquenchable passion for her, he noticed the general’s breathing quicken. Her face flushed, and she tilted her head back slightly, her lips parted as if to drink his poetry like rain drops.

When Zardrin had finished his recitation, she slowly opened her eyes and looked at him. “That was an Igruan proposal, was it not?”

“Yes. For my beloved.”

“She is a very fortunate woman, to be adored by a poet such as yourself. Imagine hearing a poem like that, knowing it is written about you. Who is she? Some Igruan noblewoman? Or I suppose saying yes to your proposal would make her such automatically. Tell me that she said yes!”

“She is my professor,” he admitted, lowering his gaze. “She … hasn’t heard the proposal yet.”

Kareth’s gaze softened. “A professor,” she said. “Does she seem unattainable? Distant?”

Zardrin nodded slowly.

“It is a hard thing,” Kareth said, “to yearn for someone who does not seem to return your love. Come, sit with me again, poet.” She patted the bench beside her, and Zardrin seated himself. “Do you think your poem can penetrate her defences?” Kareth asked. “Do you think that there might be some hidden love behind that cold, hard exterior? Is there any hope?”

“I don’t know,” Zardrin said miserably, and then he explained about his withered doveflower and the fountain flower he had inadvertently poisoned.

“Trust Pallantu not to show any care about a thing like that,” Kareth sighed.

“Is it hard, living with the speaker?” Zardrin asked.

Kareth looked away. “Not as hard as living without him,” she said quietly. “His tower has been my home for five years. I have taken my meals with him, walked in his gardens with him, listened to his poetry … after the loss of my parents, when I could not sleep, he would put me to bed himself, reciting poetry until I fell asleep and dreamed sweetly. He has been my protector, my teacher and more. But he has never written a poem about me.”

“And now you live with him no longer?”

“My eighteenth birthday present,” Kareth said bitterly, making a sweeping gesture toward the keep that rose beyond the hedge maze. “The title of general, and a fortress to live alone in, with no one to recite poetry or comfort me in the night.”

“I’m sorry,” Zardrin said.

They sat in silence for a long moment, looking at the still waters of the pond. Then Kareth rose. “I am sure you are here for work and not courtesy,” she said. “And the speaker has prepared reading for me in advance of tomorrow’s meeting with the Council. I will disturb your work no longer.”

She turned to go, then paused and turned back. “There are a number of doveflowers in Pallantu’s garden,” she said. “Not grown for anyone in particular, just growing. I will have one sent to you, soaked in Igruan wine.”

Zardrin blinked. “Really?” he said. “I mean, thank you, your grace! I mean, General.”

“Just promise me that you will take better care of this one,” Kareth said. “And that you will dare to present it to your beloved, with your poem. May you crack her façade of disinterest, dear poet. May you prove that a hard exterior may hide a warm, beating heart.”

With that said, she turned again and strode off, disappearing behind a hedge wall.

THE END

STAY BEHIND TO HELP WITH THE FOUNTAIN FLOWER

As Zardrin saw the distress in Flua’s expression, something shifted within him. His mind went to his own distress, a few years earlier, upon learning that he would have to leave his home and move to Paradisum. He had no idea why the fountain flower’s troubles could have such an effect on her, but in his heart he was sure that whatever Flua’s connection to the sick plant, a wine-soaked doveflower would be a poor replacement.

“I’m sorry,” he said again, the words carrying a new depth. “Please, Flu – Professor, allow me to help.”

As she turned her eyes from the dying plant to him, they flashed with sudden, hard anger. Then, just as suddenly, they softened.

“You didn’t know what you were doing,” she said dully.

“I did not,” he said. “And I still don’t. But I am sorry, and I beg you – I used my talent to destroy this flower. Please allow me to use it to help restore it.”

Flua looked at him for a long moment. One of the great poets might have described her gaze as “naked”, perhaps compared it to a warrior stripped of his armor or a city gate torn down. The dampness that welled up in those dark eyes made them seem larger, softer.

Then, blinking back her tears, she cleared her throat and became his professor once more. “Water,” she ordered. “From the cold spring. Use a wooden bucket. Be quick.”

Zardrin raced to the cold spring on the other side of the garden so fast that the protective hat flew off his head. A minute later, he hurried back with a sloshing wooden bucket.

When he returned, he found Flua holding another wooden bucket, frantically bailing sticky brownish sludge from the basin onto the grass. She paused only briefly, to stroke the fountainflower’s blue petals. He could feel the creative power emanating from her as she struggled to heal the plant.

“Pour it in,” she commanded, and he emptied his bucket into the basin.

“More,” she said.

But before Zardrin could run back to the spring, he suddenly realized the flaw in their strategy. “I need to undo what I did,” he said. “Otherwise, the flower will just do the same thing with the new water.”

Flua nodded, and Zardrin hastily began composing a new poem. But what words could he use? It was not often that a poet was called upon to make sweetness diminish.

“Well?” Flua said expectantly. Her hands worked quickly, gently massaging every part of the plant she could reach. Her tan-colored gardening tunic was already soaked with sticky water and dotted with dead daggerflies.

“Sorry, I need to find the right words,” he said. “Something to reduce the sweetness, to restore the plant to health. In a way that makes sense to the plant … if you see what I mean?”

“Come,” Flua said and extended a hand towards him.

He took it and found it cold and sticky and studded with dead daggerflies. But as Flua continued to stroke the fountain flower with her other hand, he felt her creator talent. It was like a gentle breeze in the back of his mind, one that both whispered and listened. Through it, he heard the distress of the plant, felt it as plainly if the ailment were in his own body. And suddenly, he could imagine what the fountain flower needed. He gathered his creative power and began to speak.

There was an old Igruan poet named Kalifer who only wrote of old love – not the flash and bursting sweetness of young passion, but the deep, gnarled tree roots of an elderly husband and wife shuffling hand in hand through their sunset years, towards their final meeting the Great Creator. Zardrin had never really understood his poetry, but now he felt he could borrow some images from it. He urged the fountain flower to reject false, hasty sweetness, to give up its intoxicating quest for fermented passion, to embrace the simplicity of what it was made to be, to reach its roots deep down into the endless love of the Great Creator and be content. He hardly knew what he was saying. But he felt it. He felt his words weave together with Flua’s warm, gentle talent, into a life-giving, healing bath around the heart of the flower.

Through Flua’s talent, he could feel the plant responding. Slowly, the rare flower stopped poisoning itself in its eager effort to produce fermented sweetness, and its nectar returned to a patient, healthy flow.

Zardrin stopped reciting at the same moment that Flua stopped massaging the plant. They stood in silence for a moment, staring at the fountain flower that was now restoring itself instead of destroying itself. It was a perfect moment, and Zardrin felt as if his heart, which had been holding its breath for longer than he could remember, released a deep, contented sigh.

But the plant still needed help. “Water,” Flua urged. “Keep filling it with the new, and I’ll keep emptying the old.”

Zardrin obediently ran back to the cold spring. It took several trips, but eventually, the basin was full of clear, healthy water. He and Flua were equally soaked as she returned to massaging the plant and he recited a few more gentle poems about health.

“We did it,” Flua said at last with a contented smile. “My fountain flower is going to live and thrive. I can feel it. Thank you, Zardrin. You cannot imagine how much this flower means to me. It was a gift from my grandfather.”

As Zardrin listened contritely, his professor opened her heart to him and explained. The fountain flower was her last living memory of her grandfather, a childhood gift to celebrate her newly-discovered creator talent, the only plant that she had managed to take with her when she had moved from Igru to study at the Academy. As Zardrin listened, it suddenly occurred to him that for the first time, she was speaking Igruan with him, the mother tongue that they shared and never used. He listened. And when she had told him everything, he explained his thoughtlessness, the pressure of his mother’s hopes, his family’s humiliation – and Flua listened.

The sun had set by the time she squeezed his shoulder sympathetically, told him she understood, and then excused herself to go take part in a meeting with the other professors.

When she had left, he finally checked the bottle in his gardener’s bag. Even in the fading light and through the tinted glass, he could clearly see the condition of the doveflower. It had wilted.

Silently, Zardrin dug a small hole in the mulch at the foot of the basin and buried his wilted proposal there. Then he stood gazing for a while at the precious plant that he and Flua had restored to life together. In that quiet moment, it was as if the clear, cool water, drawn through the hidden root, patiently transformed and poured out as healthy nectar, eased his frustration and comforted him in his grief.

It occurred to him that this day might be the first day he had ever truly loved Flua.

Should Zardrin …

Savor the moment? (THE END)

Go make preparations for the next day’s work?

TRY TO FAIL

Zardrin got to work pretending to look busy. He found a plant far from where everyone else was working – a simple hornleaf – knelt beside it, cupped his hands around its crown of jagged leaves and began to whisper. To the casual observer, it would look as if he were using a poem to try to turn the hornleaf into some kind of daggerfly killer. In reality, he was thinking aloud, whispering his worries about the doveflower in his bottle and his coming proposal.

The hornleaf listened patiently as he explained the fact that he had less than two hours to soak his prize in the traditional Igruan wine bath, and then a mere twenty-four hours to present it to his lady love as part of his formal proposal. However, despite its exceptional listening skills, the plant had no advice to offer him, not about the proposal, and not about the wine.

He had none in his room at the Academy, of course, and asking an instructor would be absurd. Here at the Academy, students were not allowed wine.

But the Academy did have an excellent, fully-stocked kitchen, and a little Igruan wine was often used as an ingredient in fancy desserts. At least that’s what his grandmother had always told him, and back when they had lived on the family’s last manor in Igru, she had often used a few drops in her delicious cakes.

As Zardrin was considering whether his grandmother might still have some Igruan wine at home and whether he could make it to her on time, a shadow fell across him.

He looked up and found himself confronted by a pair of piercing blue eyes.

“Igruan poets are famous for their inventive wordplay,” Pallantu said dryly. “But this strikes me as perhaps a bit too inventive. What exactly do you hope to accomplish by whispering to that little hornleaf?”

Zardrin’s mind raced. He prayed to the Great Creator that the speaker had not overheard anything he had said to the plant.

“Well, ummm, of course the hornleaf looks harmless,” he stammered. “But that’s exactly why I chose it.”

Pallantu raised an eyebrow.

“It, well, um, Mr. Speaker, it should look harmless to the daggerflies so that it can, ummm … catch them off-guard, if you see what I mean.”

Pallantu’s eyes narrowed, and Zardrin felt his heart stop beating for a moment. Then the speaker shook his head and strode off to another part of the garden.

When the hour was over, Zardrin was not the winner. Which was just as well, since he was in a hurry to soak his flower. As soon as Flua had dismissed the class, while the poor winner had to stay behind and discuss details with the speaker, Zardrin raced inside to consider his next move.

Should Zardrin …

Go home and ask his grandmother?

FEIGN ILLNESS AND SLIP AWAY

“Ouch!” Zardrin cried, slapping his arm. “Oh no, Professor – I think I’ve been bitten by a sparkfly! I’m deathly allergic! I must get to the infirmary at once. So sorry! Please apologize to the speaker from me.”

He turned and fled before Flua could respond.

The Academy’s gardens covered a large area – larger, in fact, than they should. The inner courtyard where they were located was vaster than the entire colossal red brick building, seen from the outside. It must have been landscaped by someone with an incredibly powerful creator talent – or perhaps the Academy had been designed by an equally powerful architect. However it had come about, there was plenty of room for Zardrin to make his way to an entrance without coming anywhere near his classmates or their prestigious guest.

The hedge maze helped. After two years of working in this garden for four days each week, Zardrin knew which paths to take to make sure there was at least one leafy green wall between him and the ongoing lesson at all times. He took a right at a topiary sculpture shaped like a fish, then a left, leaped over a bed of red hopeblooms, charged across the bridge over the fish pond, took a left into a little grove of cloudapple trees, and after making his way through a complicated bit of hedge maze, finally arrived at one of the less-frequented entrances. Thankfully, the door was unlocked.

Panting heavily, he stepped into the coolness of the broad marble corridor and closed the door behind him.

He patted his leather gardening bag. The jar felt whole inside it. He opened the bag to check. The stopper was still sat snugly in place, and the flower was safe inside. Raising the red glass jar to the light, he frowned at it thoughtfully. Would Flua have been able to make out the species at a glance? It seemed all too clear to him, but of course he already knew what it was.

And he knew that it needed wine. But where would he find some? He had none in his room at the Academy, of course, and asking an instructor would be absurd. Here at the Academy, students were not allowed wine.

But the Academy did have an excellent, fully-stocked kitchen, and a little Igruan wine was often used as an ingredient in fancy desserts. At least that’s what Grandmother had always told him, and back when they had lived on the manor in Igru, she had often used a few drops in her delicious cakes.

Should Zardrin …

Go home and ask his grandmother?

GO HOME AND ASK HIS GRANDMOTHER

Before embarking on the trip across the city, Zardrin made a quick trip to his room to change out of his heavy gardening clothes. His room here was simpler than back home, to his mother’s indignation. She had specifically requested that he be given one of the royal suites, since their family was, in fact, nobility. The headmistress had rejected the request, but Zardrin didn’t mind. The room had everything that he needed. Except the right wine.

After changing into the white clothes that were both more fashionable here in Paradisum and easier to run in, Zardrin’s gaze fell on the worn leather book on his desk. His poems. He had torn out so many pages over the course of his quest to compose the perfect poetic proposal for Flua. And now he was convinced that he had one. Or at least, one that he could make no improvement on. The realization that he would soon be reciting it to her made him feel lightheaded. He thrust the thought aside and focused on the task at hand. “The greatest romance is a thousand small labors, carried out one at a time,” his grandmother had once read to him. And right now his labor of love was to find the right wine.

He checked himself in the mirror before heading out. Aristocratic. His red hair was certainly wavy today, and his pimples were in full force. He smiled his most winsome smile, one he had practiced just for Flua. He hoped that a gap between one’s two front teeth was considered as romantic in her part of Igru as it was in his.

Zardrin shouldered his gardener’s bag with its precious cargo, checked his reflection one last time and hurried out.

The journey along the broad streets of Pallantor was like a dream. Zardrin felt as if he were floating between the great white marble buildings as he jogged all the way to the slightly less great part of the city where his mother and grandmother lived.

Thankfully, his mother was not at home. She would hardly have been happy to see him skipping a lesson, and of course she would not be sympathetic towards his errand. She had told him in no uncertain terms that his future wife was to be a member of the nobility. Preferably no less than a countess.

But Flua was more than any countess in his eyes, more than a princess, even. Grandmother understood this, even if Mother did not.

The old woman’s face lit up, and she rose from her chair and did a little dance of glee when Zardrin burst into the living room red-faced and panting and asked about the wine. For a moment it was as if she were her old self – but then she staggered, and he hastily caught her.

She insisted on being present as he soaked the flower, giving him instructions and making sure he did it properly.

“Is your poem really ready, my dear Zardrin?” she kept asking him. “And have you chosen the right occasion to present it? You’ll have to act quickly, you know. Within twenty-four hours – or the flower will blacken.”

“I know, Grandmother,” he told her. And, “Yes, Grandmother, I have a plan.” He had two plans, in fact – but he could not bring himself to explain them. He feared that if he tried, she would hear the uncertainty in his voice, and her present bout of good spirits might end.

Should Zardrin …

Try to get a moment alone with Flua on the field trip to Bloomington the next day?

Visit her window at night and read his poem?

VISIT HER WINDOW AT NIGHT AND READ HIS POEM

Like most professors, Flua had a room in the Academy, and Zardrin had long ago figured out which of the many windows was hers. It was on the second floor, facing the Academy’s small outer garden to the west.

Late that evening, he stood on the grass, barefoot as was customary for a nobleman confessing his love, and stared up at her darkened window. She was in her room. He had watched the window grow dimmer as she had blown the lamps out, one by one, behind the curtain. And unless she was a quick sleeper, she should still be awake. Was she thinking of him, he wondered as he gazed up at her window. Was she lying in bed remembering his piercing green eyes, his shock of red hair, his poetry? She had expressed appreciation for his poetry before. She had stood and watched and listened as he had spoken a drooping fireflower back to health. That had been a simple, innocent poem, about strength and sunshine. But she had been moved. He had seen it in her eyes. In that moment, she had let her guard down, forgotten to be his teacher, let herself be a woman, impressed by a young nobleman only a handful of years younger than herself.

He clung to that memory, used it to fight against the doubts that struggled to steal his courage and drag him down into the black chasm of despair. It was possible, he realized, that he had misunderstood. That Grandmother had misunderstood. That the gap in his teeth was not irresistible, that his poetry would not make any woman swoon, that no one cared about some vague noble title that was no longer backed by any lands after the money had disappeared, never to return, just like his father. It was possible that this was all a terrible mistake.

He squeezed his eyes shut, shook his head and focused on the first line of his poem. His poetry would not fail. It never failed. In fact, it was almost unfair of him to use it against his beloved this way. But in love, as in life, nothing was fair and everything was fair. So said the romantic epics.

Zardrin took a deep breath, opened his eyes and cast about for some suitable stone – no mere, tiny pebble, but one that would make enough noise to draw the attention of his beloved. He found it quickly. Fortune was with him. He pressed his lips to the stone and whispered a few lines encouraging it to be true. Then he took a final deep breath and hurled it with all his lovesick might.

The stone was true.

Unfortunately, his aim was not.

The window next to Flua’s shattered with a crash. A cry rang out in the night, and a face appeared in the window. It belonged to the Academy’s professor of martial arts, a deadly little man named Harito who could almost certainly end a young nobleman’s life in a thousand ways using only his bare hands.

The broken window opened outward, and the enraged professor swung one leg out into the night. Zardrin watched in horrified fascination as the man’s bare foot found purchase among the bricks that made up the Academy’s facade.

Then, realizing what was happening, he turned and fled for his life.

Thankfully, the black-and-white-clad city guards caught him before Harito did. And the jail cell where they brought him really wasn’t that bad, apart from the fact that they let his mother come and visit him. The shame in her voice and in her eyes was unbearable.

His grandmother, on the other hand, could not be prouder. “A deed worthy of a romantic epic,” she said as she lowered herself, with the guard’s help, into a chair that had been placed outside the bars of his jail cell especially for her. “Your lady love will hear the tale one day, and she will be overwhelmed by your passion for her! Just make sure not to do it again.”

“But Grandmother,” Zardrin said, fighting back tears, “my flower – the guards took it.”

“Zardrin,” Grandmother said firmly, “look into my eyes now, and listen carefully. You will grow another one, my boy. You will grow another one.”

THE END

CHECK THE KITCHEN

The kitchens were larger than Zardrin would have guessed. They were also busier. After making his way across the empty dining hall toward the delicious aromas wafting from the kitchen door, he carefully opened it a crack and took a quick peek before retreating behind the door to strategize.

This wasn’t going to be easy. There were at least half a dozen chefs milling around in there, chopping things, stirring large pots, peeling vegetables and forming dumplings. Sneaking past them would have seemed an impossible prospect even if he knew where the wine was kept.

As Zardrin stood there considering this, the door suddenly flung open, striking him in the face with full force. He staggered and just barely managed to fall in such a way that his leather bag with its precious cargo was safely cushioned on his belly.

“Oh no, you poor thing! Did the door hit you? Why, it’s you, my nobleman!”

Immediately, Zardrin found himself on the receiving end of the motherly ministrations of a rotund, matronly woman who had served his meals on multiple occasions. She treated him as something of a favorite, perhaps because he often thanked her after meals with a poetry inspired by her cooking. Without fail, these simple poems had always made her giggle with delight.

Now she showed a similar kind of delight as she made sure that his face and hands were thoroughly cleaned, and then brought him through the kitchen and sat him down in a chair in the cold room in the back, with a cool piece of meat pressed against one eye.

With his free eye, Zardrin noticed a rack of bottles on a high shelf, between a large, lumpy bag and a basket of what appeared to be Lantonian apples. The bottles were unlabeled. The chefs probably knew their contents by heart.

“I don’t suppose you have any Igruan wines here?” he asked, trying to sound like he was just making conversation.

The matronly woman chuckled. “I might,” she said slightly. “But the wines here are for cooking, and for professors. Or does my sweet nobleman have some reason I should make an exception for him?”

Should Zardrin …

Change the subject and try to steal the wine when she isn’t looking?

Explain his predicament and recite a poem?

CHANGE THE SUBJECT AND TRY TO STEAL THE WINE

“No, I was just curious,” Zardrin said hastily. “I know the rules here at the Academy. But, my fair maiden, surely I am keeping you from your art?”

“My art?” the cook said with a smile.

“It would be a tragedy,” Zardrin said soberly, “if my clumsiness were to deprive the whole Academy of one of your culinary masterpieces. Accept my sincerest apologies for disturbing your sweet act of creation, dear chef, and let me delay you no longer. I will rest here a minute and then be on my way.”

The woman seemed to consider for a moment. “I don’t suppose I could have a poem?” she asked hopefully. “Something sweet for me to think on while I work on the dessert, maybe?”

Hurriedly, Zardrin composed and recited a few brief lines about her desserts. It was an easy topic for him, since he usually took two helpings – especially when she made her special moon tart.

The cook listened with closed eyes and an enraptured smile. When the poem ended, she thanked him and returned to her work with a sigh, leaving him alone in the cold room with the slab of meat on his face.

Zardrin leaped up, set the meat aside on a countertop and hastily began examining the wines. The glass bottles were all different shades of green, blue, brown and purple, but these colors told him nothing. If he wanted to find the right wine, there was only one thing to do, and he would have to do it fast.

A corkscrew lay on the shelf beside the wine rack, and with a silent apology to his poem-loving benefactress, he put it to work.

The first wine was too dry. A native Paradisian wine, he thought. The second was too sweet. The third was almost right, but lacked the subtle, musty notes of a proper Igruan wine. After tasting it three times, he decided that it was unfortunately not the right thing and opened the next bottle.

By the time he had opened the tenth bottle, he was beginning to fear that this kitchen did not have a single Igruan wine. The eleventh bottle had such a strong, bitter flavor that he was forced to return to the second bottle and take a deep swig to cleanse his palate. Except he found that he had accidentally chosen the third bottle and had to try again.

The fifteenth wine had the right combination of flavors, and it was well-aged, as well. He lifted the bottle to his lips a second time, savoring the traditional Igruan wine as he fumbled with the stopper of his flower jar.

There was just enough of the wine left to soak the doveflower, after what he had drunk and the small puddle he had spilled out on the floor while pouring it.

Zardrin put the stopper back in the flower jar with some difficulty, successfully stowed the precious plant back in his leather bag on his second attempt, and turned to make his exit.

Then, remembering all the open wine bottles he had left on the counter, he turned back to recork them. But something went wrong. It was as if his legs, eager to run off and make preparations for meeting his lady love, resisted turning back around, got tangled up with each other or with his stool or something and, failing him utterly, dropped him in the puddle of wine on the floor.

There was a muffled cracking sound. The puddle grew larger. Dizzily, he stuck out his tongue and tasted it. Yes, good Igruan wine. It occurred to him that the puddle shouldn’t be getting bigger. Weren’t they out of Igruan wine? Hadn’t he poured it all into … Oh no …

The door to the cold room opened. A large, matronly woman towered over Zardrin like a horrified giantess, and he heard a scream.

*

The standard punishments at the Academy were suspension and hard manual labor. In Zardrin’s case, perhaps because his normal classes already involved hard manual labor, his theft of the wine was punished a bit differently.

He hated his new role as a kitchen boy. Not because the company of the chefs was disagreeable – on the contrary, his favorite cook treated him kindly and took every opportunity to spoil him with bits of dessert that the headmistress had said he was to be denied. It wasn’t the shame, either, though that was considerable, since all the students and professors at the Academy – including Flua – could watch him work, knowing full well what he was being punished for.

He hated his punishment because he often had to go into the cold room, the very place where he had gotten drunk and dropped the precious doveflower. The place where his hopes of proposing to the love of his life had been shattered.

THE END

EXPLAIN HIS PREDICAMENT AND RECITE A POEM

According to one of the great Igruan epics, ordinary passion might deal in untruths, but pure, unadulterated love spoke a simple language in which there was no deceit. Zardrin told the cook everything, about his deep love for Flua, his firm intention to make her his bride and his plan to propose in the traditional way, with a wine-soaked doveflower.

The matronly woman seemed skeptical at first, but then Zardrin recited the poem he had prepared for his proposal. She listened with closed eyes and an enraptured expression as his words painted a poor portrait of the feelings and dreams bubbling up in his heart.

When at last he had reached the end of his poem, the woman stood frozen for a moment. Then, with a deep sigh, she opened her eyes. “Oh, my dear nobleman!” she cried. “I could kiss you!” The next moment, she threw her arms around him and did just that, clasping him tightly to her bosom and pressing her lips to his cheek. “If only I were thirty years younger,” she said wistfully, looking deep into his eyes. “Or even just twenty years.” Then, with another sigh, she released him.

Zardrin stood speechless for a moment. This was the first time a woman outside his family had kissed him, he realized. Might it be a good omen?

Meanwhile, the cook turned to the rack of wines on the shelf and pulled down a bottle. “I happen to have some Igruan red here,” she said. “Now, the rules about giving wine to students are clear: I would lose my job. But,” she added with a wink, seeing Zardrin’s distraught expression, “there’s no rule against giving wine to flowers.”

Zardrin’s heart leaped within him, and he found himself pulling the woman into another embrace.

“Oh, my dear nobleman,” she said, stroking his back gently. “Just promise me that you will succeed. I can’t bear the thought of her breaking your poor, lovely heart.”

Zardrin cleared his throat. “I will do my best,” he said.

“That’s all anyone ever can do,” the cook said sadly, releasing him. “But if she turns you down, come to me right away and tell me. No missing meals or going off to wander the wilderness alone or whatever you Igruan poets do. You come straight here to the kitchen and tell me. Can you promise me that?”

“I promise,” Zardrin said. He would have said anything in that moment, as the matronly cook uncorked the bottle of Igruan wine before him.

She handed it to him, and he got to work eagerly. She watched, fascinated, as he unstoppered the flower jar and soaked the fresh-cut doveflower. Once the top of the flower was covered, he jammed the stopper back into the mouth of the jar and stowed his proposal gift in his leather gardener’s bag.

After thanking the cook, he headed off to make his preparations. Now he had twenty-four hours to make his proposal. He felt far from ready, but as a great Igruan poet had once said, love is an enemy no general can prepare for.

Should Zardrin …

Visit Flua’s window and propose that night?

Try to get a moment alone with her on the field trip the next day?

TRY TO GET A MOMENT ALONE WITH HER ON THE FIELD TRIP THE NEXT DAY

Zardrin had heard stories about Bloomington, even before leaving his domain to move to Paradisum. It was Paradisum’s original capital city, founded by Angelica, the domain’s original chief creator. Some said it was the peak of Angelica’s work, that its sculptures, fountains and portal stones were the finest she had created, and that its unique blend of architecture and landscaping made it one of the most beautiful cities in all of Thousandworld.

That was before the darkenwraiths had destroyed it. Now, as Zardrin’s class filed in through the broken city gate along with an escort of black-and-white-clad soldiers, he found himself gazing around in wonder at an overgrown ruin.

The legendary garden city still had a peculiar kind of beauty, but it was the beauty of dried roses in a cracked vase. The grasses, vines and bushes growing on the roofs of the reddish-brown brick buildings were decaying, the fountains were fetid pools, the graceful sculptures were missing limbs, and weeds grew freely among the cracked paving stones.

Flua had brought the class here to show them a different kind of gardening, the idea of which still remained if one studied the ruins carefully. But as she pointed out the original flowerbeds and planters, identified the species of withered plants and spoke of flowers, fruits and the juxtaposition of stone and greenery, Zardrin hardly heard a word of it. His mind was in the leather gardening bag slung over his shoulder, in the red glass jar hidden within. Today was the day.

He just needed to find a moment to get alone with Flua and make his proposal.

This was far from easy. For the first part of the day, the class traveled as one large group, flanked by soldiers. It was not until lunch, which they ate in a derelict park, that they were allowed to stray some distance from each other – but not beyond earshot and not outside the bounds of the park, which the soldiers had already searched and pronounced free of darkenwraiths.

Before dismissing them to the relative freedom of their lunch break, Flua gave her students an assignment. Each student was to find a spot that could be made particularly beautiful, and as they ate, they were to consider how they could help it to reach its potential. After lunch, each student in turn was to show his or her chosen spot to Flua and explain the work that could be done on it.

Zardrin had no appetite for the sandwich he had packed in his gardener’s bag, though he found himself taking sips from his water flask almost constantly. In this assignment, he saw a chance – perhaps the only chance he would get before the doveflower blackened.

Should Zardrin …

Look for a spot that he can make beautiful?

Look for a spot where he can speak alone with Flua?

LOOK FOR A SPOT WHERE HE CAN SPEAK ALONE WITH FLUA

The park was quite large, and Zardrin, who was completely uninterested in eating lunch, had plenty of time to search for the perfect spot. He could not make his proposal where his fellow students could see him or where a soldier could overhear his poem. So he wandered farther and farther from his classmates, through a small grove of fruit trees and past a little pond.

Eventually he reached a low stone wall that separated the park from the brown cobblestone road. This marked the boundary for the assignment. However, further along the wall, he found a gap leading across a bridge that arched over the road, to another park on the other side. The bridge was covered in dirt and grass. An extension of the same park, technically speaking.

Zardrin looked around and saw a pair of girls sitting on a rock near the orchard, and a black-and-white-clad soldier patrolling by a small pond. No one was looking in his direction.